Throw people together, give them a task, give them some skills and guide them to figure it out. It’s the process of figuring it out where they do some of the intense learning that gets incorporated into their lives. That is very much an Outward Bound approach.

Jerry Rosen

As a teenager in the early 1960’s, in suburban Baltimore, Jerry Rosen was innately drawn to the outdoors. For several years he lobbied his parents to let him go on a 28-day Outward Bound summer expedition he had read about in a magazine. At 16, he boarded his first-ever flight to Minnesota and the unfamiliar wilderness. The experience ended up changing his life in profound ways.

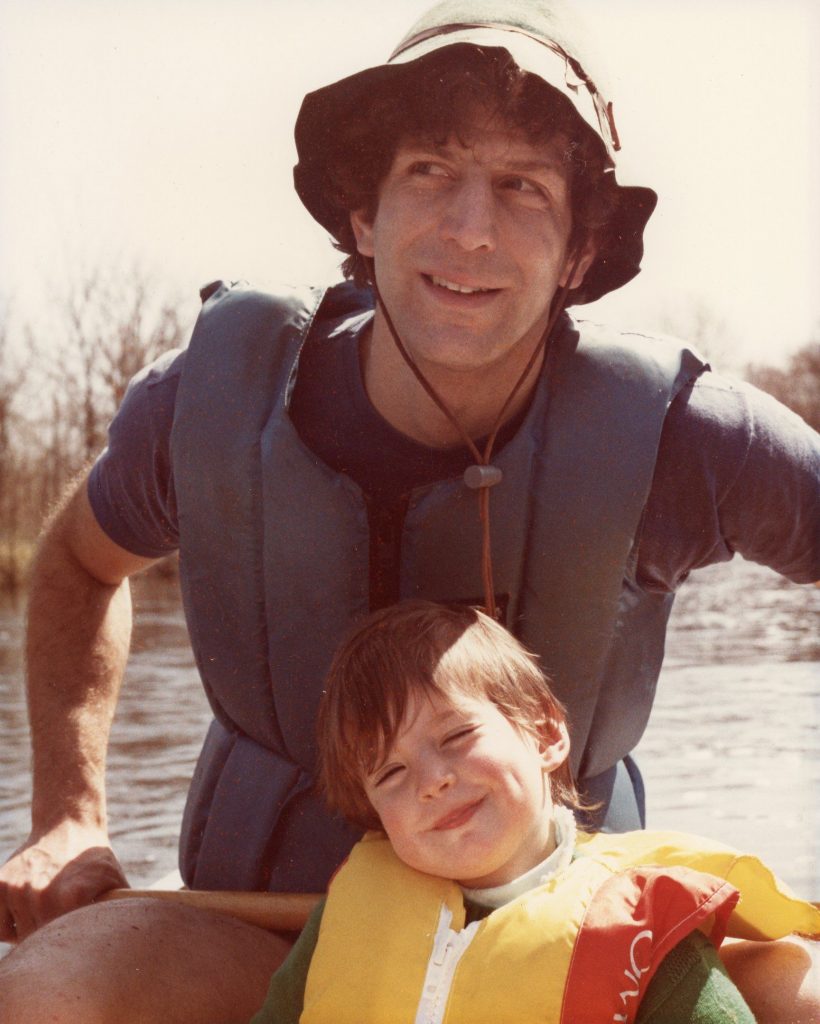

Jerry went on to become a pediatrician, Outward Bound instructor, medical liaison, Safety Committee member, Board Member and stalwart donor. Along the way, he and his wife Martha moved to Minnesota and raised their children on outdoor adventures in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) and beyond. When Jerry came upon extended and intense life challenges, he drew on important lessons from his VOBS experience to help him face the moment.

Here’s our interview with Jerry Rosen.

Q. Tell us about your first experience on course at Homeplace in the mid-1960’s.

Jerry: My Homeplace expedition was the first time I was physically pushed. The experience was really hard and I didn’t do especially well. I have a memory of portaging with a tumpline around my forehead lugging a heavy backpack. I was looking straight down, trying to bear the weight, and I wandered off the portage and suddenly found myself in the woods off the trail. I eventually got found.

I also remember my first Solo, which was three days alone.* We were given no food, three matches and a tarp. They checked on me once a day, but otherwise I was really on my own for the first time in my life. It was a scary but useful time. I caught a couple crayfish. It was probably the first time that I recognized the importance of connection with family. I had never had the opportunity to be homesick before. It was a powerful feeling.

*Solo has been a big part of the Outward Bound experience. Today on course, students are provided a secluded spot to reflect alone, with all the food, skills and supplies they need, and are monitored by staff throughout the experience to maintain safety. The Solo experience provides an important break from the rigors of the expedition and gives students the opportunity to reflect on their Outward Bound experience. The duration of Solo depends on the course length and type, as well as the competency and preparedness of the student group. Students find that Solo provokes profound and powerful learning in a short period of time and often becomes one of the most memorable parts of their Outward Bound course.

I remember our Final, where the group was totally independent, managing the food and navigation. By last night of our Final, we had eaten all the food except for a box of chocolate cake mix. I remember it was a cold, wet, rainy day and we couldn’t start a fire. Our last meal on trail was cake mix, stirred with water, sipped out of a cup. When we finally came into Homeplace, we were feeling pretty triumphant. I remember thinking that this had been an important experience, but wasn’t sure of its impact until much later on.

Q. What other wilderness experiences have you had since then?

It just lit a spark that has continued to be a real touchstone.

Jerry: Outward Bound was one of my first experiences with real wilderness. It just lit a spark that has continued to be a real touchstone. And northern Minnesota planted a seed as a very magical place for me.

During college, I did a lot of solo travel, including a cross country hitchhiking trip. I was comfortable being on my own out in the woods in national parks and the wilderness. I met my wife, Martha Brand, during coursework at MIT. As I pursued medical school, Martha was getting a law degree. Together, we became summer instructors at MOBS, Minnesota Outward Bound School, now VOBS, in 1970. At that time, we worked with Founding Executive Director Bob Pieh, and Ted Moores, Program Director. After staff training, Martha and I went back to Detroit to get married, and then returned to go out on different month-long courses that very summer.

As a pediatric resident at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., I created a summer field rotation for myself teaching one of the first MOBS courses focused on adolescence. Martha and I continued to teach at MOBS, and in 1979, we met up with a MOBS friend in Alaska for a six-week kayak trip in the central Brooks Range. It was the first of many significant wilderness trips for us.

Q. What are some highlights of your VOBS Board and committee experience?

Jerry: Martha and I had developed a love of the northern Minnesota environment, and in 1980, we settled in the Twin Cities where I became part of the pediatrics faculty at Hennepin County Medical Center (now Hennepin Healthcare). Soon after, I connected with Derek Pritchard, then MOBS Executive Director, and joined the Safety Committee as a medical consultant. I then joined the Board of Directors, where I’ve served off and on for the past 40 years.

A few of the things I’ve enjoyed most in my role on the Safety Committee are training field staff and developing safety curricula. I like being available to front line instructors when they need medical consultations, as these are some of the most significant decisions they’ll make in the field. One of the things I especially enjoyed was the opportunity to get out in the field. I joined in winter staff training for short trips. This was my first introduction to winter camping and dog sledding. I also remember remarkable wilderness trips in Canada and Mexico. Once, Martha and I went as students on a 10-day reconnaissance trip in the Copper Canyon in Mexico. In the end, the site was not deemed suitable to become a VOBS location, but we had an amazing time in a beautiful part of the world.

Q. How has VOBS grown during your tenure?

Jerry: I’ve seen the transformation of VOBS through affiliation with other Outward Bound schools, disaffiliation, and the creation of the Twin Cities Center. The Twin Cities Center is focused on working with metro city schools and non-profit partners to broaden the reach of VOBS programs. It also pioneered particular social-emotional learning elements into the curriculum under the guidance of Poppy Potter, then Program Director and current Development Director. These were important innovations.

Most recently, COVID-19 has been a central focus of our Safety Committee work and has necessitated changes in protocol. We’ve spent lots of time trying to understand how to provide safe programming in the pandemic environment. It’s a moving target. Our Safety Committee has a prominent role working with VOBS leadership to keep up with COVID-19 best practices.

Q. What do you think makes VOBS unique?

Jerry: I have been very impressed with Jack Lee’s leadership. He has kept focus on both immediate risk mitigation during COVID and staff retention. More than anything else, what VOBS offers is a staff that is uniquely qualified to deliver the program. Our staff are the core of the program–how theory gets translated into action. During COVID and its challenges, Jack prioritized staff retention.

It’s become clear throughout my tenure that the frontline of safety at VOBS is the staff. Without top quality staff, we can’t fulfill the mission. I think that accounts for the unique place that VOBS has within the Outward Bound system. As a school, we have prioritized staff in a special way by creating a welcoming environment that is a draw.

Q. Aside from the fact that you moved to Minnesota, how have your VOBS experiences impacted your life?

Jerry: We have three children. Our oldest, Sarah (now 41), went on her first Boundary Waters canoe trip at three-months old. All of our kids have grown up with camping, hiking and paddling trips. Our approach to child rearing was based on the premise that the world is full of risks and the kids won’t be protected from all of them. They need to learn to both rely on themselves and each other. We gave them just enough supervision but also the room to explore their world. Through these experiences, they learned to rely and count on one another. (Even though they would fight with each other as siblings do.) That’s probably the most important thing they’ve learned.

That is so clear to me now. I just returned from Boston, where one of my granddaughters (Sarah’s daughter) is in intensive care having just received a stem cell transplant. Sarah’s two brothers showed up, one all the way from Tanzania, because they wanted to be there for their sister. They have shown up throughout their niece’s illness.

At least some of that impetus comes from very early on, learning to rely on each other for support when things are tough. That is very much an Outward Bound approach. Throw people together, give them a task, give them some skills and guide them to figure it out. It’s the process of figuring it out where they do some of the intense learning that gets incorporated into their lives. As a parent, it is a very sweet thing to see in practice.

I think the other big thing that VOBS has influenced is my personal life. My wife Martha has Alzheimer’s disease and has had a slow, painful decline over the past 12 years that I’ve witnessed. She’s transformed from someone who supervised a dozen lawyers and led an environmental nonprofit, to someone who isn’t able to dress herself. And at the same time, we have our granddaughter who is seriously ill.

What I’ve found is you need to show up. You need to be there for people who are important to you. The fact is that it’s hard, but that doesn’t change the facts on the ground. It’s clear what you need to do. I’m naturally a very solo, self-reliant person who doesn’t instinctively draw on others for helping me solve my problems. In the last five years, it’s clear that going solo won’t lead to a successful outcome.

I’ve been able to grow in ways that we’d like the students at VOBS to grow. Lately, I’m getting better at identifying people in my world I can recruit as allies to help with what is too hard for me to do by myself. I’ve grown more in the last five years through these challenges. Things aren’t easy now, but I’m able to get up every morning with strength to face the day. And that is not a guarantee.

Q. What motivates you to support VOBS philanthropically?

Jerry: I believe in what VOBS is selling. That the wilderness itself is an important environment and that wilderness travel can be a tool to help individuals build self-reliance. Ultimately, that has served me well. It wasn’t obvious right away, but I really attribute my ability to manage the challenges that I had no idea that would be set in front of me to the basic skill set that I first started learning in Outward Bound. I personally benefited from that, and that has led me to support the organization with my work on the Board and Safety Committee and also with my dollars. As philanthropy became something I was financially capable of, I wanted my philanthropic dollars to follow my life and reflect my values.

I believe in what VOBS is selling. That the wilderness itself is an important environment and that wilderness travel can be a tool to help individuals build self-reliance… It wasn’t obvious right away, but I really attribute my ability to manage the challenges that I had no idea that would be set in front of me to the basic skill set that I first started learning in Outward Bound.

Q. What are your hopes for the future of VOBS?

Jerry: I hope VOBS will stay true to the mission using the model that we have to create resilient, empathic individuals who are ready to face whatever the future is going to throw at them. And to provide that for a wider and wider spectrum of students. Offering courses to a broad range of kids of all backgrounds and financial means. My hope is that VOBS will continue to be in a number of different environments, because they’re each unique. The challenge is maintaining the same feeling of being part of a family even through growth.

Jerry and Martha are still exploring. It’s difficult for Martha, but Jerry notices that a lot of the skills she has been practicing for decades are hard wired in. On a recent downhill ski trip in Big Sky, Montana, Martha and Jerry were able to ski the intermediate runs together with the help of an adaptive ski program. They recently completed a 10-day sea kayak trip with friends in Baja, Mexico, where they camped on the beach and snorkeled.